17.5 Focus groups

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify key considerations when planning to use focus groups as a strategy for qualitative data gathering, including preparations, tools, and skills to support it

- Assess whether focus groups are an effective approach to gather data for your qualitative research proposal

Focus groups offer the opportunity to gather data from multiple participants at once. As you have likely learned in some of your practice coursework, groups can help facilitate an environment where people feel (more) comfortable sharing common experiences which can often allow them to delve deeper into topics than they may have individually. As people relate to what others in the group say, they often go on to share their responses to these new ideas – offering a collaborative synergy. Of course, similar to the research vs. clinical interview described above, the purpose of the focus group is much different than that of the therapeutic, psychoeducational, or support group. While other elements (e.g. information sharing, encouragement) may take place, the aim of the focus group must remain anchored in the collection of data and that should be made explicitly clear so participants have accurate expectations. As a cautionary note, the advantages discussed above should be the reason you choose to use a focus group to collect data. You should not choose to conduct a focus group solely out of convenience. Focus groups require a considerable amount of planning and skill to execute well, so it is not reasonable to think that just because a focus group allows you to collect data from multiple participants at once that it is an easier option for data gathering.

Group assembly

Assembling your focus group is an important part of your planning process. Generally speaking, focus groups shouldn’t exceed 10-12 participants. When thinking about size, there are a couple things to consider. On the lower end, you do want enough participants so that they don’t feel pressure to be constantly speaking. If you only have a couple of focus group members, it loses most of the collective benefit of the focus group approach, as there are few people to generate and share ideas. On the higher end, you want to avoid having so many participants that not everyone gets to be heard and the group conversation becomes unwieldy and hard to manage.

As you are forming your group, you want to strike up a balance between heterogeneity (difference) and homogeneity (sameness) between your group members. If the group is too heterogeneous, then opinions may be so polarized that it is hard to have a productive conversation about the topic. People may not feel comfortable sharing their opinion or it may be difficult to gain a common understanding across the data. If the group is too homogeneous, then it may be hard to get much depth from the data. People may see the topic so similarly that we don’t gain much information about how differing perspectives think about the issue. You generally want your group composition to be different enough to be interesting and produce good conversation, but similar enough that members can relate to each other and have a cohesive conversation. Along these lines, you also need to consider whether or not your participants know each other. Do they have existing relationships? If they do know each other, we need to anticipate that there may be existing group dynamics. This may influence how people engage in discussion with us. On one hand, they may find it easy to share more freely. However, these dynamics may inhibit them from speaking their mind, as they might be concerned about repercussions for sharing within their social network.

As a final note on group composition, sometimes we make decisions on group members’ characteristics based on our topic. For instance, if we are asking questions about help-seeking and common experiences after (heterosexual) sexual assault, it may be challenging to host a mixed-gender group, where participants may feel triggered or guarded having members of the opposite gender present and therefore potentially less open to sharing. It is important to consider the population you are working with and the types of questions you are asking, as this can help you to be sensitive to their perceptions and facilitate the creation of a safe space. Other issues, such as race, age, levels of education, may require consideration as you think about your group composition.

Related to feelings of safety, the setting you select for your focus group is an important decision. Much like with interviews, we want participants to feel as comfortable and at-ease as possible, however, it is perhaps less common to use someone’s home for the purpose of a focus group because we are often bringing together people who may not know one another. As such, try to select a place that feels neutral (e.g. some people may not feel comfortable in a church or a courthouse), accessible, convenient, and that offers privacy for participants. If you are working with a particular group or community, there may be a space that is especially relevant or familiar for people that may work well for this purpose. A community gatekeeper or other knowledgeable community member can be an excellent resource in helping to identify where a good space might be. Seating in a circle will help participants to share more easily. Focus group organizers often provide refreshments as an incentive and to make participants feel more comfortable. If you decide to provide refreshments, be sensitive to issues like common dietary restrictions and cultural preferences.

Roles of the researcher(s)

Ideally, you are conducting your focus group with a co-researcher. This is important because it allows you to divide up the tasks and makes the process more manageable. Most often, one of you will take on the main facilitator role, with responsibilities for providing information and instructions, introducing topics, asking follow-up questions and generally structuring the encounter. The other person takes on a note-taking/processing role. While not necessarily silent, they likely say very little during the focus group. Instead, they are focused on capturing the context of the encounter. This may include taking notes about what is said, how people respond or react, other details about the space and the overall exchange as a whole. They will also often be especially attentive to group dynamics and capturing these whenever possible. Along with this, if they see that certain group members are dominating or being left out of the conversation, they may help the facilitator to address or shift these dynamics so that the sharing is more equitable. Finally, if something arises where a participant becomes upset or there is an emergency where they need to leave the room, having a co-researcher allows one of you to remain with the group, while the other can attend to the person in distress. For consistency sake, you may want to maintain roles throughout data collection. If you do decide to alternate roles as you conduct multiple focus groups, it is important that you both conduct the respective roles as similarly as possible. Remember, research is about the systematic collection of data, so you want your data collection to follow a consistent process. Below is a chart that offers some tips for each of these roles. Table 18.2 presents compares the role of facilitator to observer.

| Main Facilitator | Observer |

|

|

Focus group guide and preparations

As in your preparation for an interview, you will want to spend considerable time developing your focus group guide and the questions it contains. Be sure the language you use in your questions is appropriate for the educational level of your participants; you will need to use vocabulary that is clear and not “jargon”. At the same time, you also want to avoid talking down to your participants. You will probably want to start with some easier, non-threatening questions to help break the ice for the group and help get folks comfortable talking and sharing their input. Be prepared to ask questions in a different way or follow up with probes to help prod the conversation along if a question falls flat or fails to elicit a dialogue. In addition, you will want to plan introductions, both to the study and to one another. Usually we stick to first names, and occasionally during introductions, participants will share how they are connected to the topic of the research. Just like in many practice-related groups, facilitators usually take time to review group norms and expectations before getting started with questions. Some common norms to discuss are:

- Not talking over other participants

- Being respectful of other participants’ contributions

- All people are expected to participate in the conversation

- Not pressuring people to respond to a question if they are uncomfortable

- Using respectful language and avoiding derogatory, discriminatory or accusatory language or tone

- Not using electronic devices and silencing cell-phones during the focus group

- Allowing others ample time to contribute to the conversation and not dominating the discussion

Another expectation to address that is especially important to include is confidentiality. It is important to make clear to participants that what is shared in the group should be kept confidential and not discussed outside the context of the focus group. Additionally, it is important to let participants know that while the researchers ask all participants to protect the confidentiality of what is shared, they can’t guarantee that will be honored. Below figure 17.4 offers an example of a focus group guide template to help you think about how to structure this type of document.

|

Welcome & Housekeeping

Guidelines

Focus Group Questions I will introduce each of these questions and allow people to respond with their thoughts, viewpoints, and perspectives. Please allow a person to finish their thought before stating your own. I may invite people directly to contribute to the conversation if we have not heard from you; if you would prefer not to share at that time, feel free to say “pass”. I may ask you clarifying questions or request that you explain an idea further for me and I may ask the larger group their response to something that has been shared. Let’s get started. Question 1 Probe 1A Probe 1B Question 2 Probe 2A Probe 2B Probe 2C Probe 2D Debriefing Thank you so much for joining us today and sharing your thoughts about ___________. If you would like to learn more about our project as it progresses or if you have any questions about the results of today’s discussion, we would love to hear from you! Here is a card with my contact information so you can reach me. Email is the fast way to get through to me. If anything we talked about was upsetting and you feel like you need to speak with someone, as a reminder, you can reach out to _______________. Again, it has been our pleasure to meet with you today. |

Capturing your data

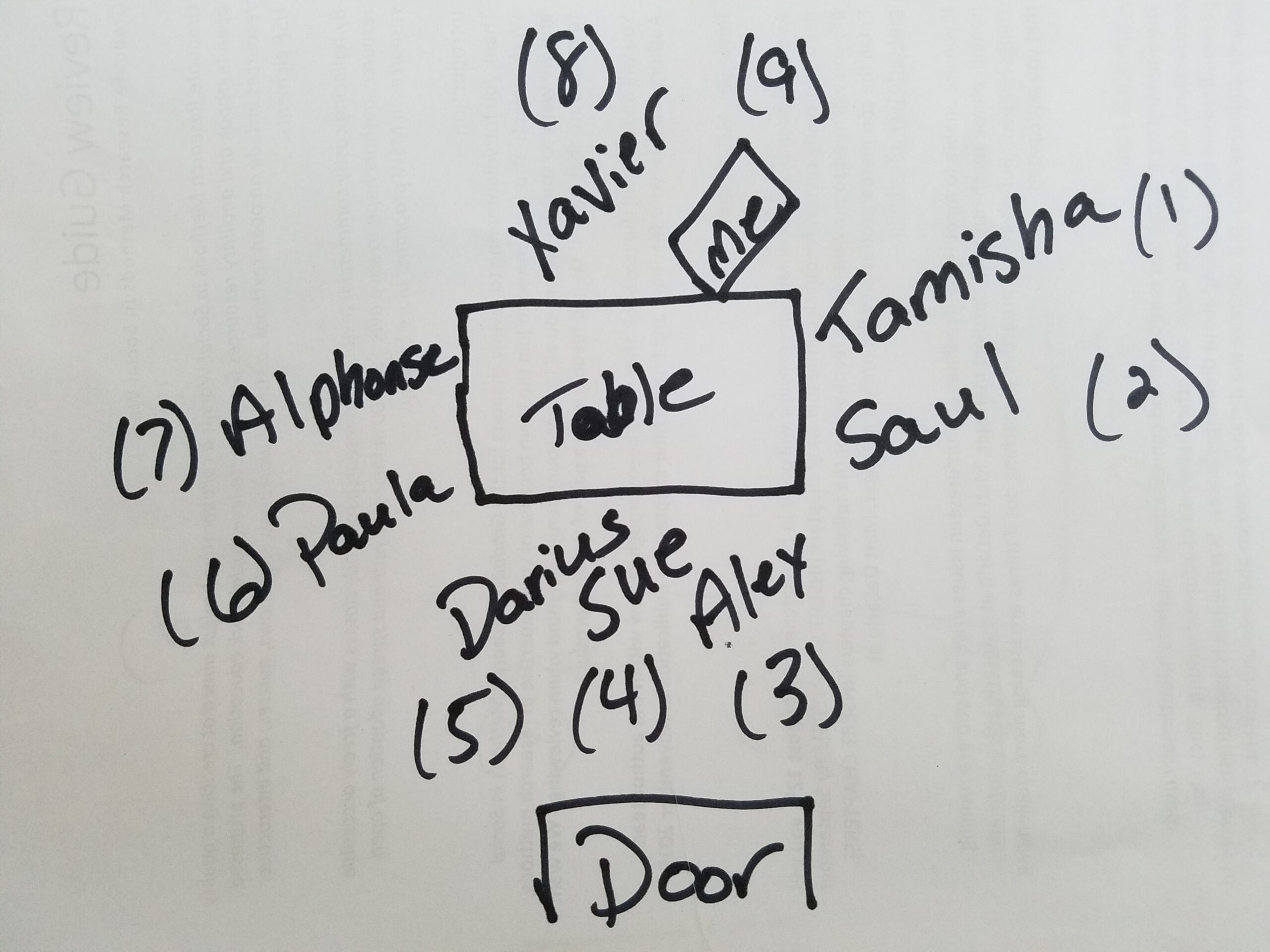

Finally, as with interviews, you will need to plan how you will capture the data from your focus group(s). Again, you may choose to record the focus groups, take field notes, or use a combination of both. There are some special considerations that apply to these choices when using a focus group, however. First, if recording, anticipate that it may be especially challenging when transcribing the recording to determine who said what. In addition, the quality of the recording can become a challenge. Despite requests for individuals to speak one at a time, inevitably there will be spots where there are multiple people talking at once, especially with an animated group. Additionally, do test the recording devices, ideally in the space you will be using them. You want to make sure that it can pick up everyone’s voice, even if they are soft-spoken and seated a distance from the device. If you are relying solely on a recording and there is a problem with it, it can be difficult to surmount the barriers this can pose. If this occurs with an interview, while not ideal, you can re-interview a person to replace the information, but re-creating a focus group can be a logistical nightmare. When taking field notes, it is a good practice to make a quick seating chart at the beginning so you can make quick references for yourself of who is saying what (see Figure 17.5). Regardless of what system you use to stay organized in taking these notes, make sure to have one that works for you. The conversations will likely happen more rapidly and will include multiple voices, so you will want to be prepared in advance.

Key Takeaways

- Focus groups offer a valuable tool for qualitative data collection when the topic we are exploring might best be understood through a group discussion that helps participants verbally process and consider their experiences, thoughts, and opinions with others.

- Details like focus group composition, roles of co-facilitators, and anticipation of group norms or guidelines require our attention as we prepare to host a focus group.

Exercises

Reflexive journal prompt

How do you feel about conducting a focus group?

- What about it is appealing

- What about it seems challenging

- Would you prefer to be the main facilitator or the observer (and why)?

- What might make using a focus group a good choice for your specific research question?

- What might make using a focus group a poor choice for your specific research question?

Resources to learn more about conducting Focus Groups.

Leung, F. H., & Savithiri, R. (2009). Spotlight on focus groups.

Duke, ModU (2016, October 19). Powerful concepts in social science: Preparing for focus groups, qualitative research methods

Onwuegbuzie et al. (2009). A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research.

Nyumba et al. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2008). Qualitative Guidelines Project: Focus groups.

A few exemplars of studies employing Focus Groups:

Foote, W. L. (2015). Social work field educators’ views on student specific learning needs.

Hoover, S. M., & Morrow, S. L. (2016). A qualitative study of feminist multicultural trainees’ social justice development.

Kortes-Miller, K., Wilson, K., & Stinchcombe, A. (2019). Care and LGBT aging in Canada: A focus group study on the educational gaps among care workers.

A form of data gathering where researchers ask a group of participants to respond to a series of (mostly open-ended) questions.

Someone who has the formal or informal authority to grant permission or access to a particular community.

A document that will outline the instructions for conducting your focus group, including the questions you will ask participants. It often concludes with a debriefing statement for the group, as well.

For research purposes, confidentiality means that only members of the research team have access potentially identifiable information that could be associated with participant data. According to confidentiality, it is the research team's responsibility to restrict access to this information by other parties, including the public.

Notes that are taken by the researcher while we are in the field, gathering data.