21.5 The future of research is open

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define open access and open science and describe how they impact social justice

- Reflect on the ways in which lack of access to scientific data and methods impacts social work practice and research

This textbook is free and openly licensed for a reason. As a writing team, our project models the vision for knowledge sharing and production we want to see in the world. The future of social work research should be as open as possible—enabling access and transformational engagement with knowledge needed to fulfill the mission of our profession. In this concluding section, we will discuss open access and open science as the building blocks of a more equitable and inclusive social work research arena.

Open access & open science

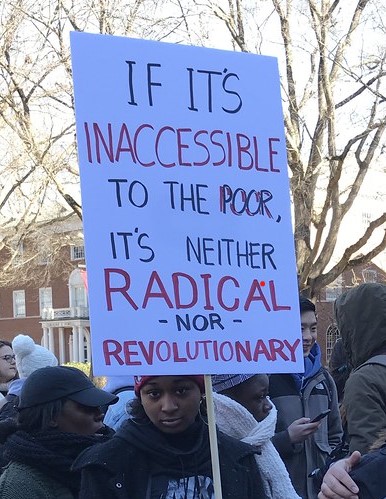

Embracing open practices can facilitate the creation of practitioner-researchers. Open access brings the promise of immediate, free access to research evidence contained in journal articles. Open access is about more than evidence and results but the advances in theory, methodology, and others that result from increasing access to knowledge. Practically speaking, all but the most recent research can be archived in a repository like Socarxiv or a university repository under publisher’s open access policy (Pendell, 2019).[1] Self-archiving, as a practice, would provide immediate public access to print-ready copies of journal articles. Open access is an ethical mandate, and social work’s near-total rejection of it renders most social work scholarship invisible to graduates, practitioners, and anyone unaffiliated with a well-funded university library. The ethical mandate to share research and resources free of cost can be almost entirely fulfilled with minimal effort by researchers today under existing open access policies of traditional journals as well as open access journals. All researchers would need to do is deposit a manuscript for each article they have published or plan to publish in the future.

Under the Open Science Framework (OSF), papers in SocArXiv can point directly to a project site created by the researchers to house data, instruments, and methods. Ideally, this project page would house auditable research data, instruments, and procedures. This is the promise of open science—replication, verifiability, and collaboration. OSF projects are designed to house all but the most sensitive class of data and resources in a cloud storage that can be privately shared among collaborators or publicly available. Researchers choose which components of their project, if any, should be publicly available as the project transitions towards dissemination.

Integrating openness into the practice of social work research requires a revision of the timeline for publication. The general rule is “as open as possible, as closed as necessary.” Openness is certainly not of greater value than confidentiality, anonymity, and the protection of research participants and clients. However, working within existing ethical boundaries, there are many possibilities for open sharing.

Corker (2021)[2] provides a detailed open science workflow—from project planning through sharing your results—for graduate students and early career researchers. This may sound advanced, but the instructions and background she provides is exception in its depth and ease of understanding.

- Pre-registering hypotheses and publishing registered reports of the study’s methods and measures.

- This helps make sure researchers do not change their hypotheses or procedures to match their data or selectively report the results that support their hypotheses.

- Creating project documents and using storage practices that protect confidential information and clearly differentiate between content that is appropriate for public view and that which must remain with the research team. This includes providing clear documentation of how data were collected, cleaned, and analyzed, including a codebook and the computer code for quantitative analyses.

- Researchers share their data so other researchers can ensure it was analyzed correctly, propose new questions and conduct new analyses, and incorporate the data with similar studies and conduct a meta-analysis.

- Using open copyright licenses (e.g., Creative Commons licenses) in sharing the data, study information, and journal articles by publishing open access.

- Facilitating a community discussion using social media, collaborative annotation, and other open platforms through public interest scholarship.

- Archiving conference presentations, reports, and other products that translate research for different audiences.

It is worth considering how open science practices may be used to integrate science and social work in a more meaningful way. First and foremost, it would eliminate the paywalls that render most research relevant to social workers inaccessible. At the same time, agency-based data is also inaccessible to both researchers and other practitioners. It is shared with grant funders, board members, and administrators, but not in a way that invites secondary analysis. Given that most schools of social work continue to use expensive statistical software such as SPSS and SAS, rather than free, open source software like R, the production of social work research knowledge remains structured by ability to pay. Using open practices, social work agency-based practitioners can create and share information about outcomes and processes, engage in immediate dialogue with the research literature, and collaborate on joint implementation projects.

In this way, open practices also have the potential to further bridge the gap between academic and practice realms. As another example, the core team behind this textbook are social work researchers, both in academia and in non-profit or government research institutions. This authorship structure is intentional. It introduces the role of researcher to students as a visible arena of social work practice, and it helps our materials be relevant outside the classroom to real social work research practitioners. Sharing resources and data openly facilitates this collaboration across academia and practice realms. Open licenses are an invitation to collaborate, to build off the work of colleagues.

Collaboration and cooperation are not guaranteed, though. Open licenses are not a silver bullet and they require participation and stewardship by community members. Even if open practices were perfectly adopted overnight—granting access to the knowledge in textbooks, journal articles, trainings on evidence-based interventions, and research data to anyone, regardless of ability to pay—the culture that drives people to share their work emerges from the actions of practitioners. Social workers, as public intellectuals and scholars, must reach beyond traditional boundaries to make social work research more accessible and participatory.

We hope that our work in this textbook has laid a foundation for the integration of research roles into your current or future social work practice. We aimed to demystify research, alleviate research anxiety, and engage students in an authentic research project relevant to their lives and future practice. We hope that your project has provided you the opportunity to build research skills that you will integrate into your life. Finally, we hope you can accept the role of lifelong scholar, dedicated to creating and engaging with knowledge relevant to your practice and life. You have the power to create knowledge and use it to transform the world. Understanding social work research means you can help people understand the lives of your clients and communities and how best to help them, fighting the many stigmas and oppressions our clients face every day.

Key Takeaways

- Open research practices have the potential to ensure access to all scientific research for anyone, regardless of ability to pay.

- Researchers should build open practices into existing research workflows, allowing their work to be accessed, replicated, audited, and transformed by other scholars.

Post-Awareness Check (Knowledge)

Now that you have completed this textbook, what have you learned about yourself as a researcher? What worked well? What would do differently next time?

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

- Look at your data and methods. Determine which elements can be ethically shared with the public and which have to remain confidential. Apply the maxim: “as open as possible, as closed as necessary.” Familiarize yourself with the rules for sharing of research data created by your IRB as well as any applicable laws like FERPA and HIPAA

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

- Familiarize yourself with the rules for sharing of research data created by your university’s IRB as well as any applicable laws like FERPA and HIPAA.

- Pendell, K. (2018). Behind the Wall. Advances in Social Work, 18(4), 1041-1052. ↵

- Corker, K. S. (2021, March 19). An Open Science Workflow for More Credible, Rigorous Research. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/wu6sn ↵

journal articles that are made freely available by the publisher

sharing one's data and methods for the purposes of replication, verifiability, and collaboration of findings

A document that we use to keep track of and define the codes that we have identified (or are using) in our qualitative data analysis.