4.2 Nomothetic explanations

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define and provide an example of a nomethetic explanation

- Describe the role of causality in quantitative research as compared to qualitative research

- Describe the difference between and provide examples of independent, dependent, and control variables

- Define hypothesis, state a clear hypothesis, and discuss the respective roles of quantitative and qualitative research when it comes to hypotheses

Nomothetic explanations are explanations that seek to be general scientific laws or universal truths. They apply to groups as a whole and not to individuals within the group who may deviate from general scientific understandings in their idiosyncratic uniqueness. Nomothetic explanations are incredibly powerful. They allow scientists to make predictions about what will happen in the future (within various margins of error, depending on the study). Moreover, they allow scientists to generalize—that is, make claims about a large population based on a smaller sample of people or items. Generalizing is important. We clearly do not have time to ask everyone their opinion on a topic or test a new intervention on every person. We need a type of explanation that helps us predict and estimate truth in all situations. Generally, a nomothetic approach tends to use quantitative research: by boiling things down to numbers, one can use the universal language of mathematics to use statistics to explore those relationships.

What do nomothetic explanations look like?

Nomothetic explanations express relationships between variables. The term variable has a scientific definition. This one from Gillespie and Wagner (2018) “a logical grouping of attributes that can be observed and measured and is expected to vary from person to person in a population” (p. 9).[1] More practically, variables are the key concepts in your research question. Simply put, the things you plan to observe when you actually do your research project, conduct your surveys, complete your interviews, etc. For now, the important thing about variables is that they vary, as in they do not remain constant. “Age” varies by number. “Gender” varies by category.

It’s also worth reviewing what is not a variable. Well, things that don’t change (or vary) aren’t variables. If you planned to do a study on how gender impacts earnings but your study only contained women, that concept would not vary. Instead, because it does not vary, it would be a constant . “Men” is not a variable, it is a constant. “Gender” is a variable. “Texas” is not a variable. The variable is the “state or territory” in which someone or something is physically located.

When one variable depends upon another, we have what researchers call independent and dependent variables. Why are they called that? Independent variables do not vary depending on other variables in the study. Dependent variables depend on independent variables. For example, in a study investigating the effect of being spanked on the severity of a child’s aggressive behavior, spanking would be the independent variable and aggressive behavior would be the dependent variable.

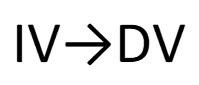

An independent variable can be considered a predictor or the cause, and a dependent variable is the outcome or effect. If all of that gets confusing, just remember the graphical relationship in Figure 4.5.

For whom and why do nomothetic explanations apply?: Moderating and mediating variables

In addition to independent and dependent variables (and control variables which we will discuss below), your study may include moderating and mediating variables. A moderating variable affects the strength and/or direction of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. These moderating variables are related to the question “For whom does this association exist?” For example, our research might find a positive association between years of job experience and income, in which people with more years of experience in a particular position make more money. However, when we include gender in our analysis, we learn that this positive association is only true for cisgender men, and not cisgender women and people of other marginalized genders. In this case, gender moderates the association between experience and income.

Mediating variables refer to the mechanisms by which an independent variable might affect a dependent variable. They are related to “How?” and “Why?” questions. For example, you might discover that there is a relationship between the degree someone attains and their income, such that people with higher degrees earn more money. As you continue your research, however, you discover that the mediating variable in your study is type of job. The degree someone earns impacts the type of job they can acquire, which in turn impacts the amount of money they earn each year. As you can see, a mediating variable is found in the causal chain between the independent and dependent variables.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

Write out your working research question, as it exists now. As we said previously in the subsection, we assume you have an explanatory research question for learning this section.

- Write out a diagram similar to Figure 4.5.

- Put your independent variable on the left and the dependent variable on the right.

Check:

- Can your variables vary?

- Do they have different attributes or categories that vary from person to person?

- How does the theory you identified in section 4.1 help you understand this association?

If the theory you’ve identified isn’t much help to you or seems unrelated, it’s a good indication that you need to read more literature about the theories related to your topic.

For some students, your working research question may not be specific enough to list an independent or dependent variable clearly. You may have “risk factors” in place of an independent variable, for example. Or “effects” as a dependent variable. If that applies to your research question, get specific for a minute even if you have to revise this later. Think about which specific risk factors or effects you are interested in. Consider a few options for your independent and dependent variable and create diagrams similar to Figure 4.5.

Finally, you are likely to revisit your working research question so you may have to come back to this exercise to clarify the causal relationship you want to investigate.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

You are interested in researching teen dating violence and teenagers’ levels of depressive symptoms and self-esteem.

Considering the working research question you developed in section 4.1:

- Write out a diagram similar to Figure 4.5.

- Put your independent variable on the left and the dependent variable(s) on the right.

Check:

- Can your variables vary?

- Do they have different attributes or categories that vary from person to person?

- How does the theory you identified in section 4.1 help you understand this association?

If the theory you’ve identified isn’t much help to you or seems unrelated, it’s a good indication that you need to read more literature about the theories related to your topic.

Developing a hypothesis

A hypothesis is a statement describing a researcher’s expectation regarding what they anticipate finding. Hypotheses in quantitative research are a nomothetic explanation that the researcher expects to be supported by their findings. A hypothesis is written to describe the expected relationship between the independent and dependent variables. In other words, write the answer to your working research question using your variables. That’s your hypothesis! Make sure you haven’t introduced new variables into your hypothesis that are not in your research question. If you have, write out your hypothesis as in Figure 4.5 (or consider if you need to revise your research question).

A good hypothesis should be testable using social science research methods. It is also specific about the relationship it explores. It will specify the independent and dependent variables and the association between them in precise terms. This can be accomplished by a thorough literature review and solid theoretical framework.

Your hypothesis should be an informed prediction based on a theory or model of the social world. For example, you may hypothesize that treating mental health clients with warmth and positive regard is likely to help them achieve their therapeutic goals. That hypothesis would be based on the humanistic practice models of Carl Rogers. Using previous theories to generate hypotheses is an example of deductive research. If Rogers’ theory of unconditional positive regard is accurate, a study comparing clinicians who used it versus those who did not would show more favorable treatment outcomes for clients receiving unconditional positive regard.

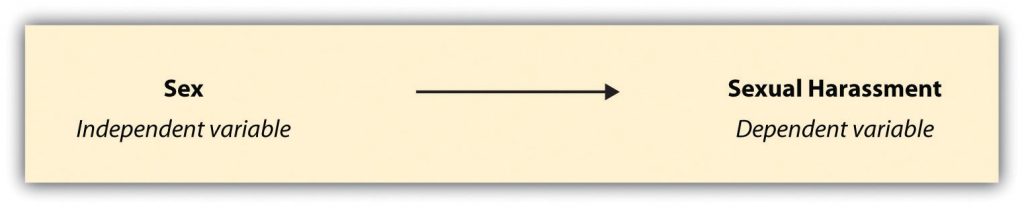

Let’s consider a couple of examples. In research on sexual harassment (Uggen & Blackstone, 2004),[2] one might hypothesize, based on feminist theories of sexual harassment, that more females than males will experience specific sexually harassing behaviors. What is the association being predicted here? Which is the independent and which is the dependent variable? In this case, researchers hypothesized that a person’s sex (independent variable) would predict their likelihood to experience sexual harassment (dependent variable).

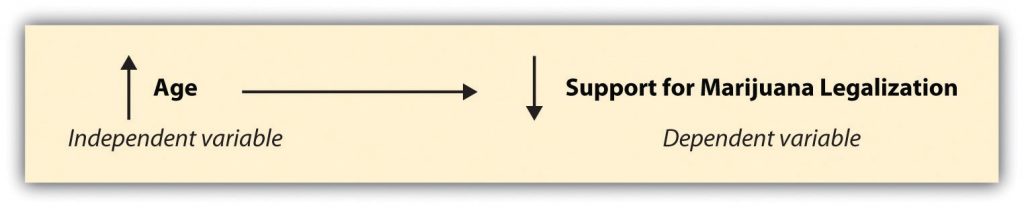

Sometimes researchers will hypothesize that a relationship will take a specific direction. As a result, an increase or decrease in one area might be said to cause an increase or decrease in another. For example, you might choose to study the relationship between age and support for legalization of marijuana.

Perhaps you’ve taken a sociology class and, based on the theories you’ve read, you hypothesize that age is negatively associated with support for marijuana legalization. A negative, or inverse, association means that as the independent (or predictor) variable changes in one direction, the dependent (or outcome) variable changes in the other direction. In this case, as age increases, support for marijuana legalization would decrease (or vice versa).

In contrast, in a positive, or direct, association, the independent (or predictor) variable and dependent (or outcome) variable change in the same direction. [3]

To restate, a direct/positive association involves two variables covarying in the same direction and an inverse/negative association involve two variables covarying in opposite directions.

If writing hypotheses feels tricky, it is sometimes helpful to draw them out and depict each of the two hypotheses we have just discussed.

It’s important to note that once a study starts, it is unethical to change your hypothesis to match the data you find. For example, what happens if you conduct a study to test the hypothesis from Figure 4.7 on support for marijuana legalization, but you find no relationship between age and support for legalization? It means that your hypothesis was incorrect, but that’s still valuable information. It would challenge what the existing literature says on your topic, demonstrating that more research needs to be done to figure out the factors that impact support for marijuana legalization. Don’t be concerned by negative results, and definitely don’t change your hypothesis to make it appear correct all along!

The hypothetico-deductive method

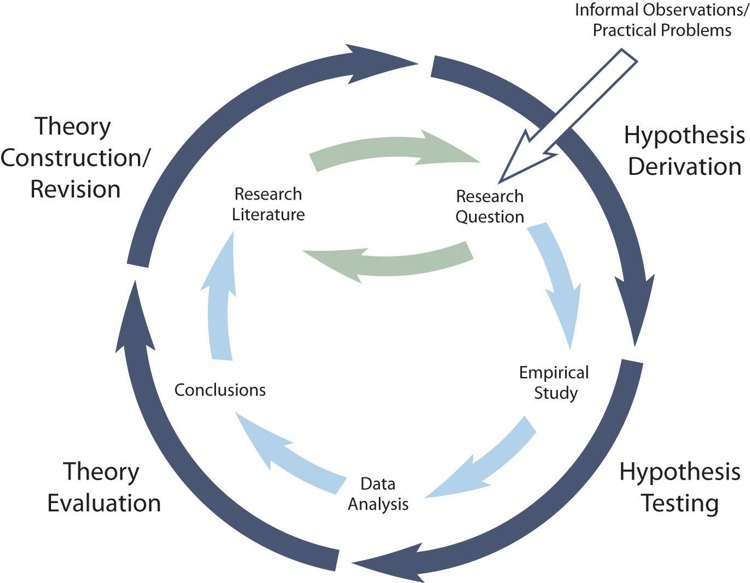

The primary way that researchers in the positivist paradigm use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). This method of scientific inquiry involves researchers choosing an existing theory. Then, they make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. (Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis). The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary.

This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 4.8 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the process of conducting a research project—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research. Together, they form a model of theoretically motivated research.

Keep in mind the hypothetico-deductive method is only one way of using social theory to inform social science research. It starts with describing one or more existing theories, deriving a hypothesis from one of those theories, testing your hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluating the theory based on the results of data analyses. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

Key Takeaways

- Nomothetic explanations focus on objectivity, prediction, and generalization.

- Dependent variables vary depending on the independent variable(s).

- Hypotheses are statements, drawn from theory, which describe a researcher’s expectation about a relationship between two or more variables.

- Wagner III, W. E., & Gillespie, B. J. (2018). Using and interpreting statistics in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. SAGE Publications. ↵

- Uggen, C., & Blackstone, A. (2004). Sexual harassment as a gendered expression of power. American Sociological Review, 69, 64–92. ↵

- In fact, there are empirical data that support this hypothesis. Gallup has conducted research on this very question since the 1960s. For more on their findings, see Carroll, J. (2005). Who supports marijuana legalization? Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/19561/who-supports-marijuana-legalization.aspx ↵

provides a more general, sweeping explanation that is universally true for all people

(as in generalization) to make claims about a large population based on a smaller sample of people or items

“a logical grouping of attributes that can be observed and measured and is expected to vary from person to person in a population” (Gillespie & Wagner, 2018, p. 9)

a characteristic that does not change in a study

causes a change in the dependent variable

a variable that depends on changes in the independent variable

A variable that affects the strength and/or direction of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

Variables that refer to the mechanisms by which an independent variable might affect a dependent variable.

a statement describing a researcher’s expectation regarding what they anticipate finding

Occurs when two variables move together in the same direction - as one increases, so does the other, or, as one decreases, so does the other

occurs when two variables change in opposite directions - one goes up, the other goes down and vice versa; also called negative association

A cyclical process of theory development, starting with an observed phenomenon, then developing or using a theory to make a specific prediction of what should happen if that theory is correct, testing that prediction, refining the theory in light of the findings, and using that refined theory to develop new hypotheses, and so on.