6.5 Critical information literacy

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define critical information literacy

- Explore the relationship between social work practice, consuming social science, and fighting for social justice

In this closing section, we hope to ground this orientation toward scientific literature in your identity as a social worker, scholar, and social scientist.

Research is a human right

When we talk about being critical in social work, we mean more than critical thinking. The core skill you are developing in the literature review portion of this textbook is information literacy, or “a set of abilities requiring individuals to ‘recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (American Library Association, 2020).[1] Information literacy is key to the lifelong learning, teaching, and research processes.

However, social work researchers and librarians dedicated to social change embrace a more progressive conceptualization of this skill called critical information literacy. It is not enough to simply know how to use the tools we use to share knowledge. Instead, social work researchers should critically examine “the social, political, economic, and corporate systems that have power and influence over information production, dissemination, access, and consumption” (Gregory & Higgins, 2013, p. ix).[2] Just like all other social structures, those we use to create and share scientific knowledge are subject to the same oppressive forces we encounter in everyday life—racism, sexism, classism, and so forth. Critical information literacy combines both fine-tuned skills for finding and evaluating literature as well as an understanding of the cultural forces of oppression and domination that structure the availability of information. As Tewell (2016)[3] argues, “critical information literacy is an attempt to render visible the complex workings of information so that we may identify and act upon the power structures that shape our lives” (para. 6).

Consider what happened in Houston, Texas. After the state took over administration of the schools from the Houston Independent School District, they planned to close libraries in some schools in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods and turn them into spaces that could be used to isolate students who were “disrupting” the classrooms (Prose, 2023).[4] David Goodman of the New York Times stated “The decision to fire librarians and effectively close libraries in some of the city’s poorest schools has been the most contentious yet made by a new set of Houston public school leaders who were imposed on the district and its 187,000 mostly Black and Hispanic students this year by the administration of Gov. Greg Abbott” (Goodman, 2023).[5] This will take away the students’ access to free information and may lead to a community of information impoverished citizens in the future.

Information privilege

From critical information literacy, we get the term information privilege which is defined by Booth (2017)[6] as:

the accumulation of special rights and advantages not available to others in the area of information access. Individuals with the resources to access the information they need, are affiliated with research or academic institutions and libraries, or live close to a public library with access to resources and services such as free interlibrary loan are examples of those with information privilege. Those who are unable to access the information they need are information underprivileged or impoverished [emphasis in original]; this includes people who are incarcerated, poor, unaffiliated with a university or research institution, or live in rural areas distant from a public library.

How can you recognize information privilege? The video from the Steely Library at Northern Kentucky University below will help you.

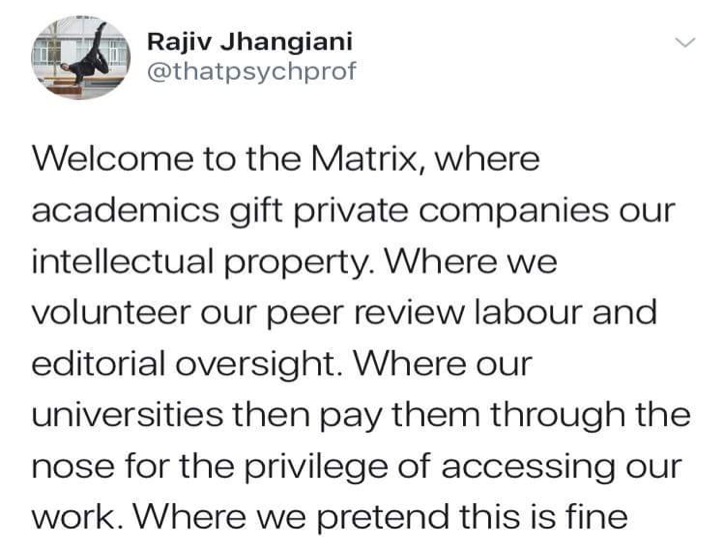

It is important to recognize your own information privilege and use it to help enact social change on behalf of those who are oppressed within the system of scholarly knowledge production and sharing we currently have. We previously discussed the issue of paywalls in this chapter. Paywalls lock away access to knowledge to only those who can afford to pay, shutting out those with fewer resources. This effect of publishing only in journals that require a paywall is endemic to social work scholarship, as Pendell (2020, 2018)[7] describes, there are few social work open access journals and social work researchers do not post open access copies of their articles even when explicitly allowed by publishers to do so. The reasons for this are not financial, as authors do not profit from the sales of journal articles. Indeed, faculty who edit, review, and author articles are not paid for their work under the current model of commercial journal publication. Scholars do not have a meaningful share in the 31.3% profit margins of Elsevier, the largest commercial publisher of scholarly journals (RELX, 2019).[8] Libraries are struggling to keep up with annual price increases. This topsy-turvy world is best encapsulated in Figure 6.2, which summarizes the problems in scholarly publication succinctly.

As we discussed at the beginning of this chapter, paywalls effectively shut out social work students from accessing journal articles after they graduate.[9] However, paywalls also shut out community members, clients, and self-advocates from accessing the research information they need to effectively advocate for themselves. This is because paywalls are an obstruction to the basic human right to access and interact with the knowledge humanity creates.

As Willinsky (2006) states, “access to knowledge is a human right that is closely associated with the ability to defend, as well as to advocate for, other rights.” The open access movement is a human rights movement that seeks to secure the universal right to freely access information in order to produce social change. Information is a resource, and the current approach to sharing that resource—the key to human development—excludes many oppressed groups from accessing what they need to address matters of social justice. Appadurai (2006)[10] conceptualizes this as a “right to research…the right to the tools through which any citizen can systematically increase that stock of knowledge which they consider most vital to their survival as human beings and to their claims as citizens” (p. 168). From a human rights perspective, research is not something confined to professional researchers but “the capacity to systematically increase the horizons of one’s current knowledge, in relation to some task, goal or aspiration” (p. 173).

In Chapter 2, we discussed action research which includes community members as part of the research team. Action research addresses information privilege by addressing the power imbalance between academic researchers and community members, ensuring that the voice of the community is represented throughout the process of creating scientific knowledge. This equity-enhancing process provides community members with access to scientific knowledge in many ways: (1) access via academic to scholarly databases, (2) access to the training and human capital of the researcher, who embodies years of education in how to conduct social science research, and (3) access to the specialized resources like statistical or qualitative data analysis software required to conduct scientific research. Moreover, it highlights that while open access is important, it is only one half of the equation. Open access only addresses how people receive scholarly information. But what about how social science knowledge is created? Action research underscores that equity is not just about accessing scientific knowledge, but co-creating scientific knowledge as partners with community members. Critical information literacy critiques the current practices of scientific inquiry in social work and other disciplines as exclusionary, as they reinforce existing sources of privilege and oppression.

This imbalance between academic researchers and community members should be considered within an English-speaking, Western context. The widespread adoption of open access and open science in the developing world underscores the extreme imbalances that international researchers face in accessing scholarly information (Arunachalam, 2017).[11] Paywalls, barriers to international travel, and the tradition of in-person physical conferences structure the information sharing practices in social science in a manner that excludes participation from researchers who lack the financial and practical resources to access these exclusionary spaces (Bali & Caines, 2016; Eaves, 2020).[12]

In the United States, the federal government has increasingly adopted policies that facilitate open access, including the National Institute of Health’s requirement that all publications from projects it funds must be open access within a year after publication in a commercial journal as well as President Obama’s open data initiative. At the time of this writing, the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC) is working with the Trump administration on a formal proposal to make all research articles published using federal grant funds accessible to the public as open access, though at the time of this writing there is no final agreement on the policy design or implementation. In Europe, Plan S is a multi-stakeholder social change coalition that is seeking structural change to scholarly publication and open access to research. Latin America and South America are far ahead of their Western counterparts in adopting open access, providing a view of what is possible when community and equity are centered in scholarly publication (Aguado-Lopez & Becerril-Garcia, 2019).[13]

The slow progress of social movement organizations to ensure free access to scientific knowledge has inspired radical action. Out of growing frustration with journal paywalls, Sci-Hub was created by a computer programmer from Kazakhstan, Alexandra Elbakyan. This resource is an illegal, pirate repository of about 85% of all paywalled journal articles in existence up to 2020, when it stopped uploading papers in compliance with an injunction from an Indian court (Himmelstein et al., 2018).[14] Sci-Hub is not legal under international copyright law,[15] yet researchers unaffiliated with a well-funded university in the developed world cannot conduct research without it. The site has moved multiple times as their domains are shut down commercial publishers whose content is illegally stored by Sci-Hub, and its founder hopes that by successfully arguing her case before and Indian court, she can continue to operate Sci-Hub legally under Indian law, and in effect, guarantee the human right to access research for free within India (Cummins, 2021).[16] Sci-Hub is a symptom of a broken system of scholarly publication that locks away scientific knowledge behind impossibly high textbook and journal paywalls. These are impossible for nearly all people to pay for in the course of a normal literature review, and thus, our broken system of scholarly publication necessitates that researchers use shadow libraries like Sci-Hub, Z-Library, and Library Genesis. It should not require mass-scale copyright infringement for the world to access scientific information.

The current model of scientific publishing privileges those already advantaged and raises important obstacles for those in oppressed groups to access and contribute to scientific knowledge or research-informed social change initiatives. For a more thorough, Black feminist perspective on scholarly publication see Eaves (2020).[17] As social workers, it is your responsibility to use your information privilege—the access you have to the world’s knowledge and the skills you gain during your doctoral education and postdoctoral professional development—to fight for social change.

Being a responsible consumer of research (Keep this section, but edit it down to be more concise)

Social work often involves accessing, creating, and otherwise engaging with social science knowledge to create change. On the micro-level, critical information literacy is needed to inform evidence-based decision-making in clinical practice. On the meso- and macro-level, social workers can use information literacy skills to give a voice for community concerns, help communities access and create the knowledge they need to foster change, or evaluate how well existing programs serving the community achieve their goals. Now that you are familiar with how to conduct ethical and responsible research and how to read the results of others’ research, you have an obligation to use your information literacy skills to create social change. This is part of critical information literacy: using your information privilege to address social injustices.

Collecting, sharing, and creating research findings for social change requires you to take seriously your identity as a social scientist. Doing so is in part a matter of being able to distinguish what you do know based on research findings from what you do not know. It is also a matter of having some awareness about what you can and cannot reasonably know.

When assessing social scientific findings, think about the information provided to you. Social scientists should be transparent with how they collected their data, ran their analyses, and formed their conclusions. These methodological details can help you evaluate the researcher’s claims. If, on the other hand, you come across some discussion of social scientific research in a popular magazine or newspaper, chances are that you will not find the same level of detailed information that you would find in a scholarly journal article. With secondary sources like news articles, it is hard to know enough about the study to be an informed consumer of information. Always read the primary source when possible.

Additionally, take into account whatever information is provided about a study’s funding source. Most funders want, and in fact require, that recipients acknowledge them in publications. Keep in mind that some sources may not disclose who funds them. If this information is not provided in the source from which you learned about a study, it might behoove you to do a quick search on the internet to see if you can learn more about the funding. Findings that seem to support a particular political agenda, for example, might have more or less influence on your thinking about your topic once you know if the funding posed a potential conflict of interest.

There is some information that even the most responsible consumer of research cannot know. Because researchers are ethically bound to keep the identity of people in our study confidential, for example, we will never know exactly who participated in a given study or sometimes even in what location it was conducted. Awareness that you may never know everything about a study should provide some humility in terms of what we can “take away” from a given report of findings.

Unfortunately, researchers also sometimes engage in unethical behavior and do not disclose things that they should. For example, a recent study on COVID-19 (Bendavid et al., 2020)[18] did not disclose that it was funded by the chief executive of JetBlue, an airline company losing money from COVID-19 travel restrictions. It is alleged that this study was paid for by airline executives in order to provide scientific support for increasing the use of air travel and lifting travel restrictions. These conflicts of interest demonstrate that science is not distinct from other areas of social life that can be abused by those with more resources in order to benefit themselves.

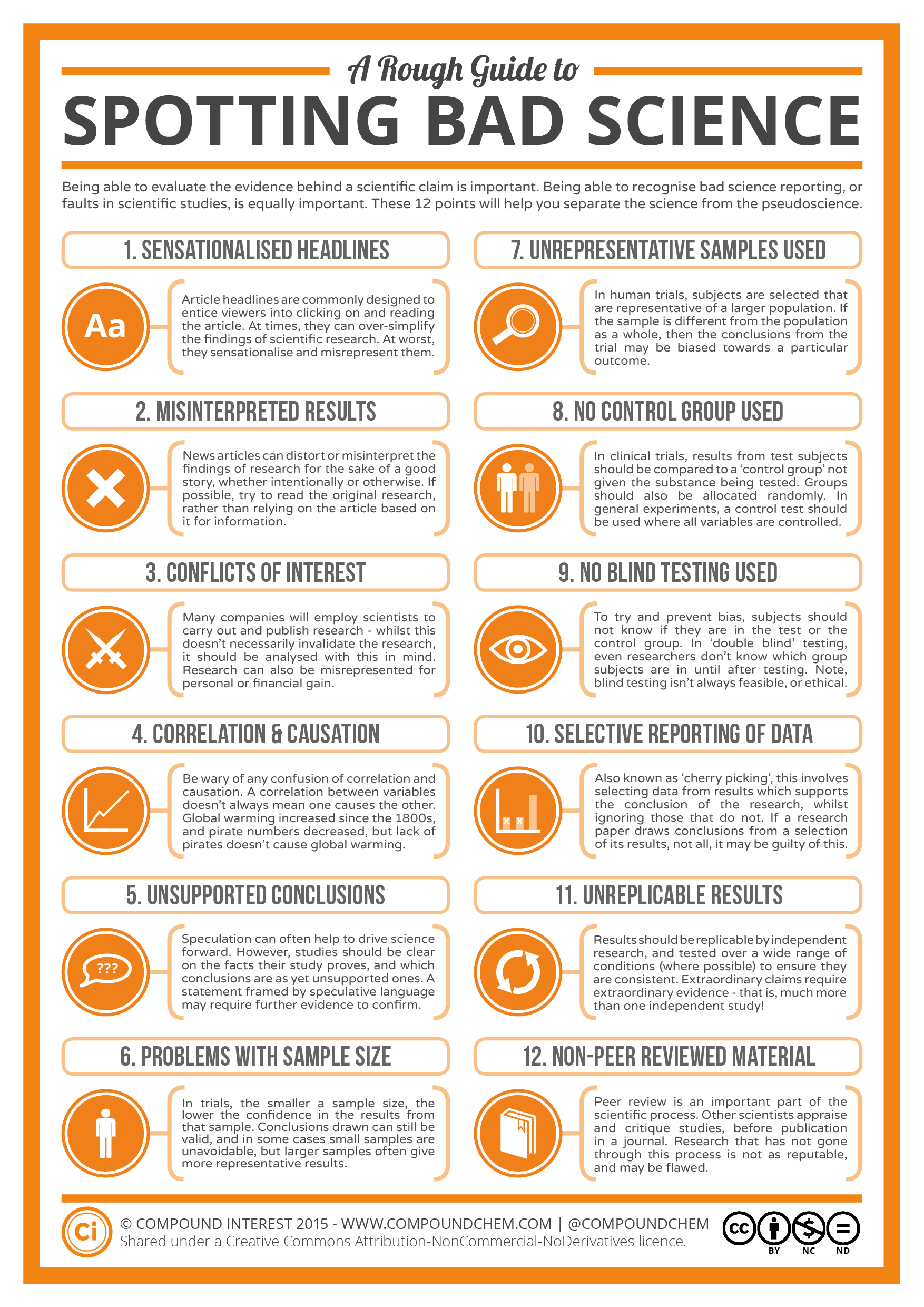

COVID-19 is a particularly instructive case in spotting bad science. In a rapidly evolving information context, social workers and others were forced to make decisions quickly using imperfect information. The Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine, two of the most prestigious journals in medicine, had to retract two studies due to irregularities missed by pre-publication peer review despite the fact that the results had already been used to inform policy changes (Joseph, 2020).[19] At the same time, former President Trump’s lies and misinformation about COVID-19 were a grave reminder of how information can be corrupted by those with power in the social and political arena (Paz, 2020).[20]

Figure 6.3 presents a rough guide to spotting bad science that is particularly useful when science has not had enough time for peer review and scholarly debate to thoroughly and systematically investigate a topic, as in the COVID-19 crisis. It is also a useful quick-reference guide for social work practitioners who encounter new information about their topics from the news media, social media, or other informal sources of information like friends, family, and colleagues.

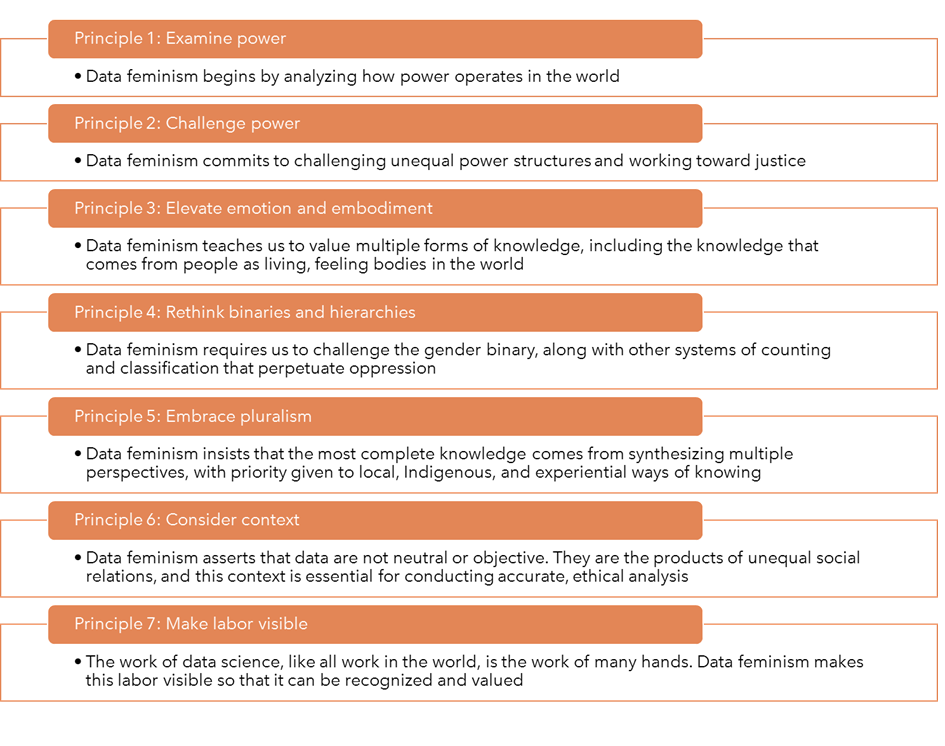

Feminist perspectives on science generally support the framework in Figure 6.4 but consider them to be incomplete, as they do not critique the scientific process itself. By drawing a line between science vs. pseudoscience, scientific inquiry can further social justice by using data to battle misinformation and uncover social inequities. However, feminist perspectives also draw our attention to historically overlooked aspects of the scientific process. D’ignazio and Klein (2020)[21] instead offer seven intersectional feminist principles for equitable and actionable COVID-19 data, as visualized in Figure 6.4.

Information literacy beyond scholarly literature

The research process we described in this chapter will help you arrive at an understanding of the scientific literature. However, that is not the only literature of value for researchers. For those conducting action research that engages more with communities and target populations, researchers are responsible not only for reviewing the scientific literature on their topic but also the literature that communities find important. If there are local newspapers, television shows, religious services or events, community meetings, or other sources of knowledge that your target population finds important, you should engage with those resources as well. Understanding these information sources builds an empathetic understanding of participating groups and can help inform your research study. Moreover, they are likely to contain knowledge that is not a part of the scientific literature but is nevertheless crucial for conducting scientific research appropriately and effectively in a community.

Key Takeaways

- At this point, you should have a folder full of articles (at least a few dozen) that are relevant to your topic. Don’t worry! You won’t read all of them, but you will skim most of them for the most important information.

- Social workers should develop critical information literacy. This helps social workers use social science knowledge for social change, and it critiques how current publishing models exclude and privilege different groups from accessing and creating knowledge.

- Social work involves helping others understand social science and applying it in your practice. You must learn how to discriminate between reliable and unreliable information and apply your scientific knowledge to benefit your clients and community.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

- Write a few sentences about what you think the answer to your working question might be.

- Identify at least five reputable sources of information from your literature search that provide evidence that what you wrote is true.

- What steps do you plan to take to demonstrate that you are helping others to understand social science and its relationship to your practice

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

- Identify three databases or sources of information from your search that could be a resource when conducting a literature review on your research topic in the future.

- How will demonstrate to others that your research topic is vital in helping others to understand social science and practice?

- American Library Association (2020). Information literacy. Retrieved from: https://literacy.ala.org/information-literacy/ ↵

- Gregory, L. & Higgins, S. (eds.) (2013). Information literacy and social justice: Radical professional praxis. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press. ↵

- Tewell, E. (2016). Putting critical information literacy into context: How and why librarians adopt critical practices in their teaching. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. Retrieved from: http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2016/putting-critical-information-literacy-into-context-how-and-why-librarians-adopt-critical-practices-in-their-teaching/ ↵

- Prose, F. (2023). Why is Houston shutting down libraries at some of its poorest schools? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/aug/15/houston-shutting-libraries-poorest-public-schools ↵

- Goodman, D. (2023). Texas revamps Houston schools, closing libraries and angering parents. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/13/us/texas-houston-schools-libraries-takeover.html ↵

- Booth, C. (2017, November 9). Open access, information privilege, and library work. OCLC Distinguished Seminar Series. Retrieved from: https://www.oclc.org/research/events/2017/11-09.html ↵

- Pendell, K. (2020, April 30). Social work’s (very few) gold OA journals. Retrieved from: https://opensocialwork.org/2020/04/30/gold-oa-journals/; Pendell, K. D. (2018). Behind the Wall: An Exploration of Public Access to Research Articles in Social Work Journals. Advances in Social Work, 18, 1041-1052. ↵

- RELX (20`19). Annual report and financial statements 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.relx.com/~/media/Files/R/RELX-Group/documents/reports/annual-reports/2018-annual-report.pdf ↵

- After a year or so, your login will no longer work with the library. It's sincerely too expensive for your university to afford lifetime access to journal articles for all graduates, though it is certainly understandable why students would expect differently. ↵

- Appadurai, A. (2006). The right to research. Globalisation, societies and education, 4(2), 167-177. ↵

- Arunachalam, S. (2017). Social justice in scholarly publishing: Open access is the only way. The American Journal of Bioethics, 17(10), 15-17. ↵

- Bali, M., & Caines, A. (2018). A call for promoting ownership, equity, and agency in faculty development via connected learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 46.; Eaves, L. E. (2020). Power and the paywall: A Black feminist reflection on the socio-spatial formations of publishing. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences. ↵

- Aguado-López, E., & Becerril-Garcia, A. (2019). AmeliCA before Plan S–The Latin American Initiative to Develop a Cooperative, Non-Commercial, Academic Led, System of Scholarly Communication. Retrieved from: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2019/08/08/amelica-before-plan-s-the-latin-american-initiative-to-develop-a-cooperative-non-commercial-academic-led-system-of-scholarly-communication/ ↵

- Himmelstein, D. S., Romero, A. R., Levernier, J. G., Munro, T. A., McLaughlin, S. R., Tzovaras, B. G., & Greene, C. S. (2018). Sci-Hub provides access to nearly all scholarly literature. ELife, 7, e32822. ↵

- We are not lawyers, and we are not giving legal advice. ↵

- Cummins, B. (2021, June 8). How academic pirate Alexandra Elbakyan is fighting scientific misinformation. Vice News. Retrieved from: https://www.vice.com/en/article/v7ev3x/how-academic-pirate-alexandra-elbakyan-is-fighting-scientific-misinformation ↵

- Eaves L. E. (2021). Power and the paywall: A Black feminist reflection on the socio-spatial formations of publishing. Geoforum; journal of physical, human, and regional geosciences, 118, 207–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.04.002 ↵

- Bendavid, E., Mulaney, B., Sood, N., Shah, S., Ling, E., Bromley-Dulfano, R., ... & Tversky, D. (2020, April 17). COVID-19 antibody seroprevalence in Santa Clara County, California. MedRxiv. ↵

- Joseph, A. (2020, June 4) ↵

- Paz, C. (2020, May 27, 2020). All the President’s lies about the coronavirus: An unfinished compendium of Trump’s overwhelming dishonesty during a national emergency. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2020/05/trumps-lies-about-coronavirus/608647/ ↵

- D'Ignazio, C., & F. Klein, L. (2020). Seven intersectional feminist principles for equitable and actionable COVID-19 data. Big Data & Society, 7(2), 2053951720942544. ↵

"a set of abilities requiring individuals to 'recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information" (American Library Association, 2020)

a theory and practice that critiques the ways in which systems of power shape the creation, distribution, and reception of information

the accumulation of special rights and advantages not available to others in the area of information access

when a publisher prevents access to reading content unless the user pays money

in a literature review, a source that describes primary data collected and analyzed by the author, rather than only reviewing what other researchers have found