8.2 Synthesizing information

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Describe how to use summary tables to organize information from empirical articles

- Describe how to use topical outlines to organize information from the literature reviews of articles you read

- Create a concept map that visualizes the key concepts and relationships relevant to your working research question

- Use what you learn in the literature search to revise your working research question

This section will introduce you to three tools scholars use to organize and synthesize (i.e., weave together) information from multiple sources. First, we will discuss how to build a summary table containing information from empirical articles that are highly relevant—from literature review, to methods and results—to your entire research proposal. These are articles you will need to know in detail.

Second, we’ll discuss what to do with the other articles you’ve downloaded. As we’ve discussed previously, you’re not going to read most of the sources you download from start-to-finish. Instead, you’ll look at the author’s literature review, key ideas, and skim for any relevant passages for your project. As you do so, you should create a topical outline that organizes all relevant facts you might use in your literature that you’ve collected from the abstract, literature review, and conclusion of the articles you’ve found. Of course, it is important to note the original source of the information you are citing.

Finally, we will revisit concept mapping as a technique for visualizing the concepts in your study. Altogether, these techniques should help you create intermediary products—documents you are not likely to show to anyone or turn in for a grade—but that are vital steps to a final research proposal.

Organizing empirical articles using a summary table

Your research proposal is an empirical project. You will collect raw data and analyze it to answer your question. Over the next few weeks, identify about 10 articles that are empirically similar to the study you want to conduct. If you plan on conducting surveys of practitioners, it’s a good idea for you to read in detail other articles that have used similar methods (sampling, measures, data analysis) and asked similar questions to your proposal. A summary table can help you organize these Top 10 articles: empirical articles that are highly relevant to your proposal and working research question.

Using annotations you make on the articles as a guide, create a spreadsheet or Word table with your annotation categories as columns and each source as new row. For example, I was searching for articles on using a specific educational technique in the literature. I wanted to know whether other researchers found positive results, how big their samples were, and whether they were conducted at a single school or across multiple schools. I looked through each empirical article on the topic and filled in a summary table. At the end, I could do an easy visual analysis and state that most studies revealed no significant results and that there were few multi-site studies. These arguments were then included in my literature review. These tables are similar to those you will find in a systematic review article.

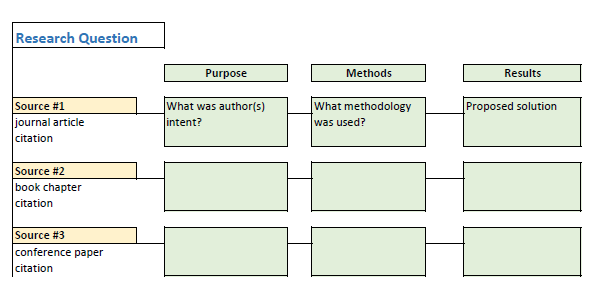

A basic summary table is provided in Figure 8.1. A more detailed example is available from Elaine Gregersen’s blog, and you can download an Excel template from Raul Pacheco-Vega’s blog. Remember, although “the means of summarizing can vary, the key at this point is to make sure you understand what you’ve found and how it relates to your topic and research question” (Bennard et al., 2014, para. 10).[1] As you revisit and revise your working research question over the next few weeks, think about those sources that are so relevant you need to understand every detail about them.

A good summary table will also ensure that when you cite these articles in your literature review, you are able to provide the necessary detail and context for readers to properly understand the results. For example, one of the common errors I see in student literature reviews is using a small, exploratory study to represent the truth about a larger population. You will also notice important differences in how variables are measured or how people are sampled, for instance, and these details are often the source of a good critical review of the literature.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

- If you have not already done so, search for and download about 10 empirical articles that are likely to be relevant to your proposed study. This may change as you revise your working research question and study design over the next few weeks. Create a list of these 10 articles that are highly relevant to your project.

- Create a spreadsheet for your summary table. Using one of the templates linked in this chapter, fill in the columns of your spreadsheet. Enter the information from one of the articles you’ve read so far. As you finalize your research question over the next few weeks, fill in your summary table with the 5 most relevant empirical articles on your topic.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

You are interested in researching the effects of race-based stress and burnout among social workers.

- If you have not already done so, search for and download about 5 empirical articles that are likely to be relevant to your proposed study.

- Create a spreadsheet for your summary table. Using one of the templates linked in this chapter, fill in the columns of your spreadsheet. Enter the information from one of the articles you’ve read so far. As time allows, fill in your summary table with information from the 5 empirical articles on your topic.

Synthesizing facts using a topical outline

If we’re only reading 10 articles in detail, what do we do with the others? Raul Pacheco-Vega recommends using the AIC approach: read the Abstract, Introduction, and Conclusion (and the discussion section, in empirical articles). For non-empirical articles, it’s a little less clear but the first few pages and last few pages of an article usually contain the author’s reading of the relevant literature and their principal conclusions. You may also want to skim the first and last sentence of each paragraph. Only read paragraphs in which you are likely to find information relevant to your working research question. Skimming like this gives you the general point of the article, though you should read in detail the most valuable resource of all—another author’s literature review.

It’s impossible to read all of the literature about your topic. You will read about 10 articles in detail. For a few dozen more (there is no magic number), you will read the abstract, introduction, and conclusion, skim the rest of the article, but ultimately never read everything. Make the most out of the articles you do read by extracting as many facts as possible from each. You are starting your research project without a lot of knowledge of the topic you want to study, and by using the literature reviews provided in academic journal articles, you can gain a lot of knowledge about a topic in a short period of time. This way, by reading only a small number of articles, you are also reading their citations and synthesis of dozens of other articles as well.

As you read an article in detail, we suggest copying any facts you find relevant in a separate word processing document. Another idea is to copy anything you’ve annotated as background information into an outline. Copying and pasting from PDF to Word can be difficult because PDFs are image files, not documents. To make that easier, use the HTML version of the article, convert the PDF to Word in Adobe Acrobat or another PDF reader, or use the “paste special” command to paste the content into Word without formatting. If it’s an old PDF, you may have to simply type out the information you need. It can be a messy job, but having all of your facts in one place is very helpful when drafting your literature review.

You should copy and paste any fact or argument you consider important. Some good examples include definitions of concepts, statistics about the size of the social problem, and empirical evidence about the key variables in the research question, among countless others. It’s a good idea to consult with your professor and the course syllabus to understand what they are looking for when reading your literature review. Facts for your literature review are principally found in the introduction, results, and discussion section of an empirical article or at any point in a non-empirical article. Copy and paste into your notes anything you may want to use in your literature review.

Importantly, you must make sure you note the original source of each bit of information you copy. Nothing is worse than needing to track down a source for fact you read who-knows-where. If you found a statistic that the author used in the introduction, it almost certainly came from another source that the author cited in a footnote or internal citation. You will want to check the original source to make sure the author represented the information correctly. Moreover, you may want to read the original study to learn more about your topic and discover other sources relevant to your inquiry.

Assuming you have pulled all of the facts out of multiple articles, it’s time to start thinking about how these pieces of information relate to each other. Start grouping each fact into categories and subcategories. For example, a statistic stating that single adults who are homeless are more likely to be male may fit into a category of gender and homelessness. For each topic or subtopic you identify during your critical analysis of each paper, determine what those papers have in common. Likewise, determine which differ. If there are contradictory findings, you may be able to identify methodological or theoretical differences that could account for these contradictions. For example, one study may sample only high-income earners or those living in a rural area. Determine what general conclusions you can report about the topic or subtopic, based on all of the information you’ve found.

Create a separate document containing a topical outline that combines your facts from each source and organizes them by topic or category. As you include more facts and more sources in your topical outline, you will begin to see how each fact fits into a category and how categories are related to one another. Keep in mind that your category names may change over time, as may their definitions. This is a natural reflection of the learning you are doing. In Table 8.1, a topical outline is presented and associated with quotes from the original sources.

| Quotes copied from an article | Topical outline: Quotes organized by category |

|

I. LGBTQ+ adolescents and suicide

“Accumulating evidence indicates that adolescents who have same-sex sexual attractions, who have had sexual or romantic relationships with persons of the same sex, or who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual are more likely than heterosexual adolescents to experience depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and to make suicide attempts (Remafedi et al. 1998; Russell and Joyner 2001; Safren and Heimberg 1999).” II. LGBTQ+ adolescents and emotional distress “Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) system showed that 40% of youth who reported a minority sexual orientation indicated feeling sad or hopeless in the past 2 weeks, compared to 26% of heterosexual youth (District of Columbia Public Schools, 2007). Those data also showed that lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth were more than twice as likely as heterosexual youth to have considered attempting suicide in the past year (31% vs. 14%). This body of research demonstrates that lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth have high levels of emotional distress.” III. Transgender adolescents and emotional distress “A much smaller body of research suggests that adolescents who identify as transgendered or transsexual also experience increased emotional distress (Di Ceglie et al. 2002; Grossman and D’Augelli 2006, 2007).” “In a study based on a convenience sample of 55 transgendered youth aged to 15–21 years, the authors found that more than one fourth reported a prior suicide attempt (Grossman and D’Augelli 2007).” |

A complete topical outline is a long list of facts arranged by category. As you step back from the outline, you should assess which topic areas for which you have enough research support to allow you to draw strong conclusions. You should also assess which areas you need to do more research in before you can write a robust literature review. The topical outline should serve as a transitional document between the notes you write on each source and the literature review you submit to your professor. It is important to note that they contain plagiarized information that is copied and pasted directly from the primary sources. In this case, it is not problematic because these are just notes and are not meant to be turned in as your own ideas. For your final literature review, you must paraphrase these sources to avoid plagiarism. More importantly, you should keep your voice and ideas front-and-center in what you write as this is your analysis of the literature. Make strong claims and support them thoroughly using facts you found in the literature.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

- If you have not already identified a review article on your topic, search for one now. If there are none in your topic area, you can also use other non-empirical articles or empirical articles with long literature reviews (in the introduction and discussion sections).

- Create a word processing document for your topical outline. Using the review article, start copying facts you identified as Background Information or Results into your topical outline, and organize each fact by topic or theme. Make sure to copy the internal citation for the original source of each fact. For articles that do not use internal citations, create one using the information in the footnotes and references. As you finalize your research question over the next few weeks, skim the literature reviews of the articles you download for key facts and copy them into your topical outline.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

You are interested in researching the effects of race-based stress and burnout among social workers.

- If you have not already identified a review article on your topic, search for one now. If there are none in your topic area, you can also use other non-empirical articles or empirical articles with long literature reviews (in the introduction and discussion sections).

- Create a word processing document for your topical outline. Using the review article, start copying facts you identified as Background Information or Results into your topical outline, and organize each fact by topic or theme. Make sure to copy the internal citation for the original source of each fact. For articles that do not use internal citations, create one using the information in the footnotes and references.

Putting the pieces together: Building a concept map

Developing a concept map or mind map around your topic can be helpful in figuring out how the facts fit together. Concept mapping during the literature review stage of a research project builds on this foundation of knowledge and aims to improve the “description of the breadth and depth of literature in a domain of inquiry. It also facilitates identification of the number and nature of studies underpinning mapped relationships among concepts, thus laying the groundwork for systematic research reviews and meta-analyses” (Lesley, Floyd, & Oermann, 2002, p. 229).[2] Its purpose, like other question refinement methods, is to help you organize, prioritize, and integrate material into a workable research area—one that is interesting, answerable, feasible, objective, scholarly, original, and clear. Consider this video from the University of Guelph Library (CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Think about the topics you created in your topic outline. How do they relate to one another? Within each topic, how do facts relate to one another? As you write down what you have, think about what you already know. What other related concepts do you not yet have information about? What relationships do you need to investigate further? Building a conceptual map should help you understand what you already know, what you need to learn next, and how you can organize a literature review.

This technique is also illustrated in this YouTube video about concept mapping. You may want to indicate which concepts and relationships you’ve already found in your review and which ones you think might be true but haven’t found evidence of yet. Once you get a sense of how your concepts are related and which relationships are important to you, it’s time to revise your working research question.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

- For your chosen topic, outline what you currently know about the topic and your feelings towards the topic. Make sure you are able to be objective and fair in your research.

- Formulate at least one working research question to guide your inquiry. It is common for topics to change and develop over the first few weeks of a project, but think of your working research question as a place to start.

- Create a concept map using a pencil and paper.

- Identify the key ideas inside the literature, how they relate to one another, and the facts you know about them.

- Reflect on those areas you need to learn more about prior to writing your literature review.

- As you finalize your research question over the next few weeks, update your concept map and think about how you might organize it into a written literature review.

- Refer to the topics and headings you use in your topical outline and think about what literature you have that helps you understand each concept and relationship between them in your concept map.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

You are interested in researching the effects of race-based stress and burnout among social workers.

- Outline what you currently know about the topic and your feelings towards the topic. How might your feelings impact your ability to be objective and fair in your research?

- Formulate at least one working research question on the topic.

- Create a concept map using a pencil and paper.

- Identify the key ideas inside the literature, how they relate to one another, and the facts you know about them.

- Reflect on those areas you would need to learn more about prior to writing a literature review.

Revising your working research question

You should be revisiting your working research question throughout the literature review process. As you continue to learn more about your topic, your question will become more specific and clearly worded. This is normal, and there is no way to shorten this process. Keep revising your question in order to ensure it will contribute something new to the literature on your topic, is relevant to your target population, and is feasible for you to conduct as a student project.

For example, perhaps your initial idea or interest is how to prevent obesity. After an initial search of the relevant literature, you realize the topic of obesity is too broad to adequately cover in the time you have to do your project. You decide to narrow your focus to causes of childhood obesity. After reading some articles on childhood obesity, you further narrow your search to the influence of family risk factors on overweight children. A potential research question might then be, “What maternal factors are associated with toddler obesity in the United States?” You would then need to return to the literature to find more specific studies related to the variables in this question (e.g. maternal factors, toddler, obesity, toddler obesity).

Similarly, after an initial literature search for a broad topic such as school performance or grades, examples of a narrow research question might be:

- “To what extent does parental involvement in children’s education relate to school performance over the course of the early grades?”

- “Do parental involvement levels differ by family social, demographic, and contextual characteristics?”

- “What forms of parent involvement are most highly correlated with children’s outcomes? What factors might influence the extent of parental involvement?” (Early Childhood Longitudinal Program, 2011).[3]

In either case, your literature search, working research, and understanding of the topic are constantly changing as your knowledge of the topic deepens. A literature review is an iterative process, one that stops, starts, and loops back on itself multiple times before completion. As research is a practice behavior of social workers, you should apply the same type of critical reflection to your inquiry as you would to your clinical or macro practice.

There are many ways to approach synthesizing literature. We’ve reviewed the following: summary tables, topical outlines, and concept maps. Other examples you may encounter include annotated bibliographies and synthesis matrices. As you are learning how to conduct research, find a method that works for you. Reviewing the literature is a core component of evidence-based practice in social work. See the resources below if you need some additional help:

Literature Reviews: Using a Matrix to Organize Research / Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota

Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources / Indiana University

Writing a Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix / Florida International University

Sample Literature Reviews Grid / Complied by Lindsay Roberts

Literature review preparation: Creating a summary table. (Includes transcript) / Laura Killam

Key Takeaways

- You won’t read every article all the way through. For most articles, reading the abstract, introduction, and conclusion are enough to determine its relevance. It’s expected that you skim or search for relevant sections of each article without reading the whole thing.

- For articles where everything seems relevant, use a summary table to keep track of details. These are particularly helpful with empirical articles.

- For articles with literature review content relevant to your topic, copy any relevant information into a topical outline, along with the original source of that information.

- Use a concept map to help you visualize the key concepts in your topic area and the relationships between them.

- Revise your working research question regularly. As you do, you will likely need to revise your search queries and include new articles.

Post-awareness check (Knowledge)

What have you learned about your research style? What are your best practices for organization of journal articles?

Have you discovered your optimum time for you to complete your research tasks? What is the length of time you can provide focused attention on your specific tasks?

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

- Look back at the working research question for your topic and consider any necessary revisions. It is important that questions become clearer and more specific over time. It is also common that your working research question shifts over time, sometimes drastically, as you explore new lines of inquiry in the literature. Return to your working research question regularly and make sure it reflects the focus of your inquiry.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

You are interested in researching the effects of race-based stress and burnout among social workers.

- Look back at the working research question for your topic and consider any necessary revisions. It is important that questions become clearer and more specific over time. It is also common that your working research question shifts over time, sometimes drastically, as you explore new lines of inquiry in the literature.

- Bernnard, D., Bobish, G., Hecker, J., Holden, I., Hosier, A., Jacobson, T., Loney, T., & Bullis, D. (2014). Presenting: Sharing what you’ve learned. In Bobish, G., & Jacobson, T. (eds.) The information literacy users guide: An open online textbook. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/chapter/present-sharing-what-youve-learned/ ↵

- Leslie, M., Floyd, J., & Oermann, M. (2002). Use of MindMapper software for research domain mapping. Computers, informatics, nursing, 20(6), 229-235. ↵

- Early Childhood Longitudinal Program. (2011). Example research questions. https://nces.ed.gov/ecls/researchquestions2011.asp ↵